BACK TO GALLERY

BACK TO GALLERY

Peter Harrington

Oskar Schindler.

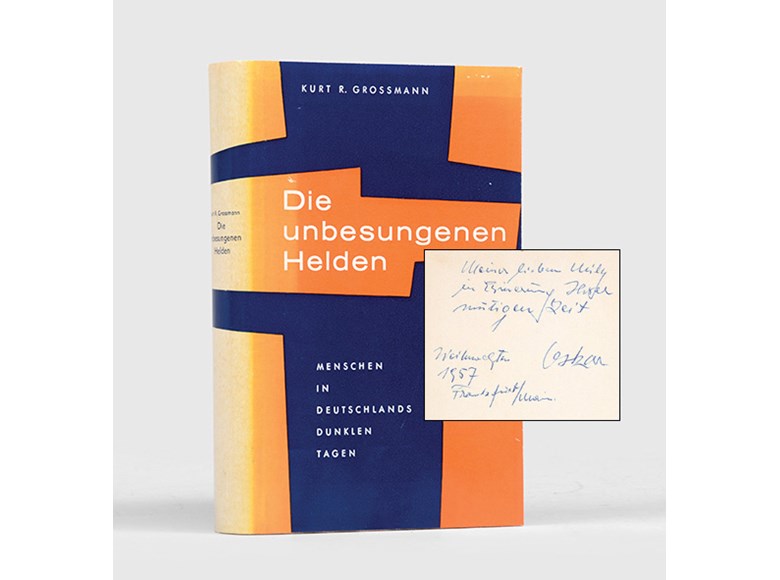

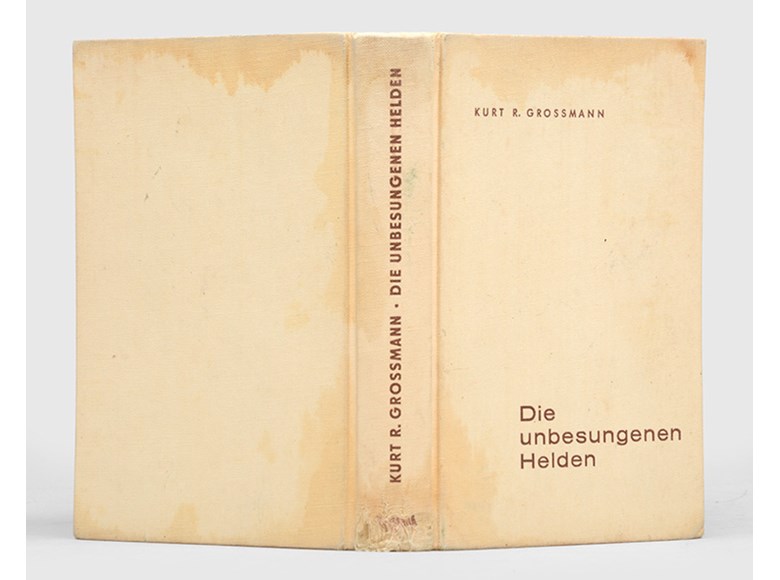

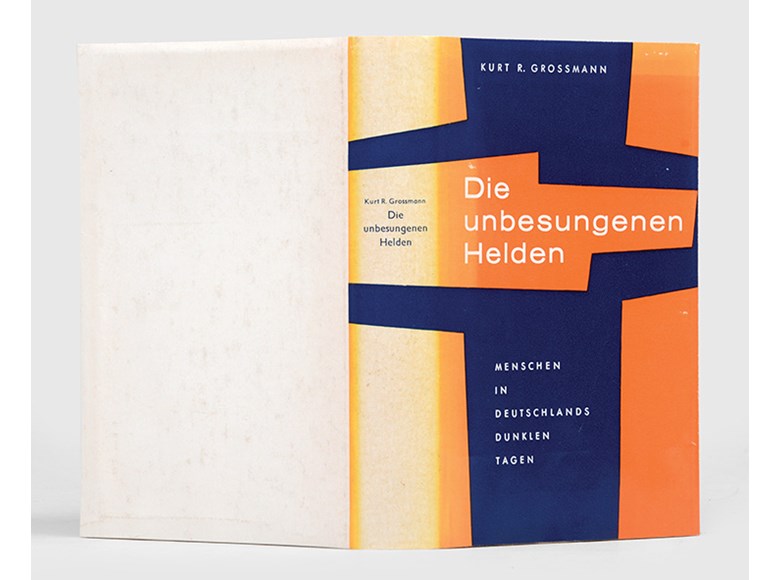

Die unbesungenen Helden. Menschen in Deutschlands dunklen Tagen (The Unsung Heroes; People in Germany’s Darkest Days).

Inscribed by Schindler to Emilie, “Mother Courage”: the published testimony of their wartime work

description

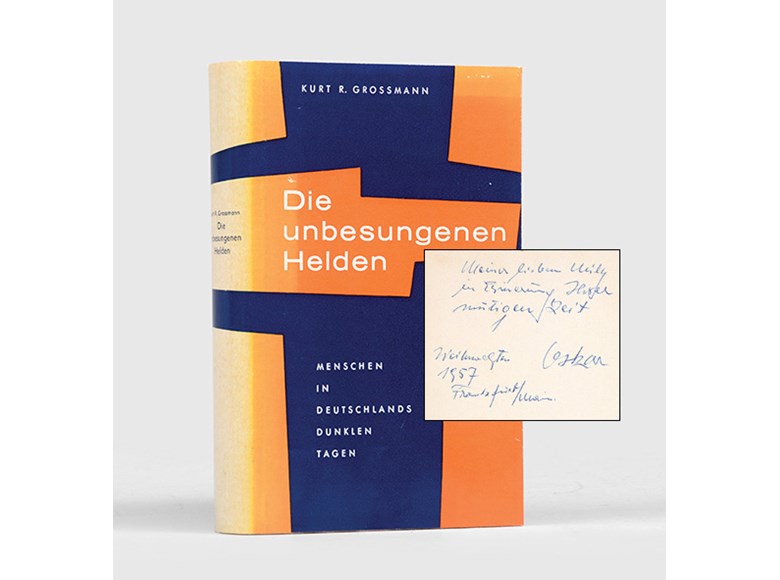

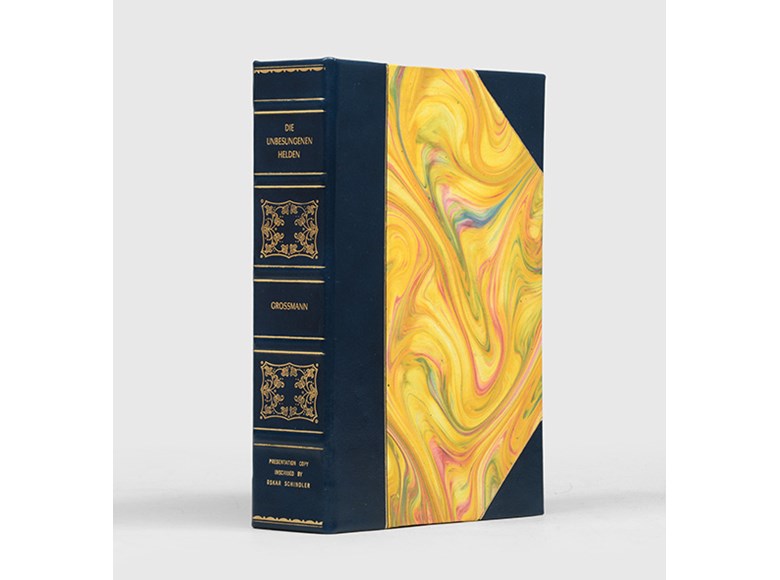

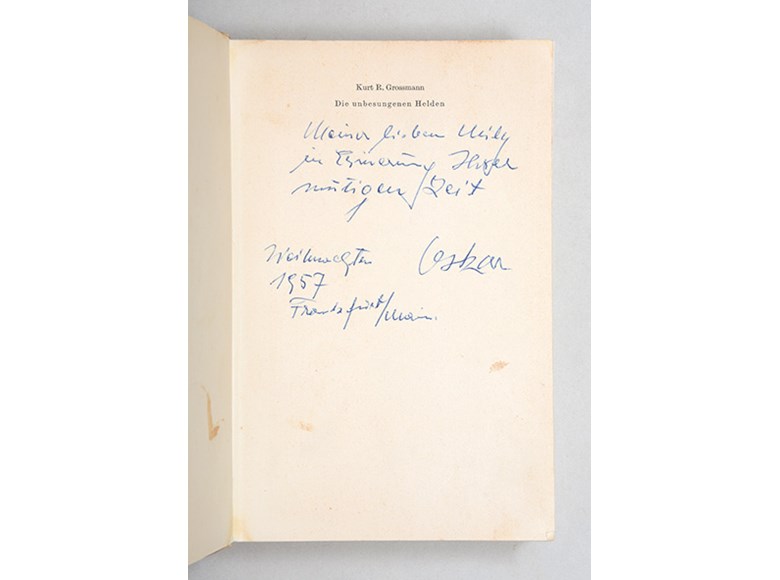

First edition, first printing, of the only autobiographical account of Oskar Schindler’s wartime work to be published, this copy an extraordinarily poignant association, inscribed to his wife, Emilie: “Meiner lieben Mily in Erinnerung Ihrer mutigen Zeit. Weihnachten 1957 Frankfurt/Main” (“To my dear Mily in remembrance of her courageous time. Christmas 1957, Frankfurt am Main”). Schindler’s testimony was never republished in his lifetime, and it was never translated into English. We have traced no other copies signed or inscribed by Schindler.

At the time of Schindler’s death in 1974, his wartime exploits were not widely known. A number of journalists had submitted pieces on his story, never to be published, and a film project had even been unsuccessfully pitched to Fritz Lang. It was evidently felt that the time was not right for the story of a “good German”, and perhaps particularly not one with the reputation as “a Nazi party member, an indifferent Catholic, a womanizer and a businessman not averse to engaging in illegal activities to increase his profits” (The Catholic Century).

Kurt Grossmann was a German Jew who had fled to the United States in 1939 and following the war was working for the Jewish World Congress in New York. In early 1948, alerted to the story by “Schindler Jews” living in America, he sent Schindler a care package together with a letter expressing his “gratitude for [his] humane behavior during the terrible Hitler years”, and asking, “Have you ever written down the story of how you saved the Jews? I would appreciate it if you could send me a copy” (Bernardi, p. 128).

Grossmann finally succeeded in getting this study published, in German only, in 1957. Schindler arrived in Frankfurt, practically destitute, on the eve of the book’s publication, leaving behind his wife Emilie in Argentina, where they had settled after the war. Oskar’s inscription, some six months later, presenting this copy to Emilie as a Christmas gift, is both poignant - he never returned to Argentina, and the couple never met again - and notable for his full acknowledgement of her invaluable work and courage.

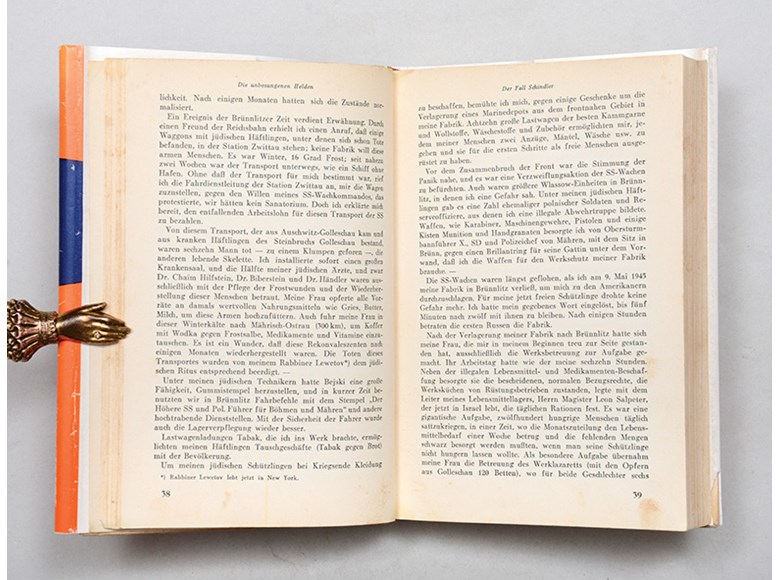

In this significant compilation of the stories of German gentiles who risked their lives to assist Jews during the Holocaust, Grossmann places “Der Fall Schindler” (”The Schindler Case”) first. After a brief introduction he offers Schindler’s narrative entirely in his own words, which are, on the whole, dispassionate, almost forensic, particularly when the nature of narrative is considered. However, when recounting Emilie’s involvement, his language becomes more emotionally persuasive. Paying tribute to her tireless work and commitment he explains that she “took on the sole task of looking after the factory ... [and] the supervision of the factory hospital ... her contempt for everything to do with the SS and the Gestapo was as great as mine, and I often became anxious when she courageously gave the highest SS leaders short shrift in concentration camp manner” (p. 39).

Despite her pivotal role alongside Oskar in saving hundreds of Jews, Emilie has been progressively written out of the story, and following the success of Thomas Keneally’s Booker Prize-winning novel Schindler’s Ark in 1983 and Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-winning adaptation in 1993, Emilie found herself further in the shadow of Oskar’s posthumous fame, as her involvement was minimized in the interests of plot efficiency. “Oskar is the hero”, she reflected in 1999, “and what about me? I saved many Jews, too”.

It seems clear from both the text of Oskar’s “report” and his inscription in this copy, that he fully recognized Mily’s contribution to the Schindler Case. They were far from an ideal couple, and his abandonment of her at this time is certainly not the behaviour of an ideal husband. However, it does seem that in this final rupture, perhaps symptomatic of the profound disruption and dislocation of the times, he is making, by way of farewell, a gesture of acknowledgement, that the book was a record of her courageous time as much as it was of his, and that between them, despite everything, they had achieved something of lasting importance.

At the time of Schindler’s death in 1974, his wartime exploits were not widely known. A number of journalists had submitted pieces on his story, never to be published, and a film project had even been unsuccessfully pitched to Fritz Lang. It was evidently felt that the time was not right for the story of a “good German”, and perhaps particularly not one with the reputation as “a Nazi party member, an indifferent Catholic, a womanizer and a businessman not averse to engaging in illegal activities to increase his profits” (The Catholic Century).

Kurt Grossmann was a German Jew who had fled to the United States in 1939 and following the war was working for the Jewish World Congress in New York. In early 1948, alerted to the story by “Schindler Jews” living in America, he sent Schindler a care package together with a letter expressing his “gratitude for [his] humane behavior during the terrible Hitler years”, and asking, “Have you ever written down the story of how you saved the Jews? I would appreciate it if you could send me a copy” (Bernardi, p. 128).

Grossmann finally succeeded in getting this study published, in German only, in 1957. Schindler arrived in Frankfurt, practically destitute, on the eve of the book’s publication, leaving behind his wife Emilie in Argentina, where they had settled after the war. Oskar’s inscription, some six months later, presenting this copy to Emilie as a Christmas gift, is both poignant - he never returned to Argentina, and the couple never met again - and notable for his full acknowledgement of her invaluable work and courage.

In this significant compilation of the stories of German gentiles who risked their lives to assist Jews during the Holocaust, Grossmann places “Der Fall Schindler” (”The Schindler Case”) first. After a brief introduction he offers Schindler’s narrative entirely in his own words, which are, on the whole, dispassionate, almost forensic, particularly when the nature of narrative is considered. However, when recounting Emilie’s involvement, his language becomes more emotionally persuasive. Paying tribute to her tireless work and commitment he explains that she “took on the sole task of looking after the factory ... [and] the supervision of the factory hospital ... her contempt for everything to do with the SS and the Gestapo was as great as mine, and I often became anxious when she courageously gave the highest SS leaders short shrift in concentration camp manner” (p. 39).

Despite her pivotal role alongside Oskar in saving hundreds of Jews, Emilie has been progressively written out of the story, and following the success of Thomas Keneally’s Booker Prize-winning novel Schindler’s Ark in 1983 and Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-winning adaptation in 1993, Emilie found herself further in the shadow of Oskar’s posthumous fame, as her involvement was minimized in the interests of plot efficiency. “Oskar is the hero”, she reflected in 1999, “and what about me? I saved many Jews, too”.

It seems clear from both the text of Oskar’s “report” and his inscription in this copy, that he fully recognized Mily’s contribution to the Schindler Case. They were far from an ideal couple, and his abandonment of her at this time is certainly not the behaviour of an ideal husband. However, it does seem that in this final rupture, perhaps symptomatic of the profound disruption and dislocation of the times, he is making, by way of farewell, a gesture of acknowledgement, that the book was a record of her courageous time as much as it was of his, and that between them, despite everything, they had achieved something of lasting importance.

SEND AN EMAIL

SEND AN EMAIL